Commodore William H. Shock

Founding Father of Rehoboth Beach?

Prominent Civil War Veteran Retires to Summer “Cottage” in Rehoboth

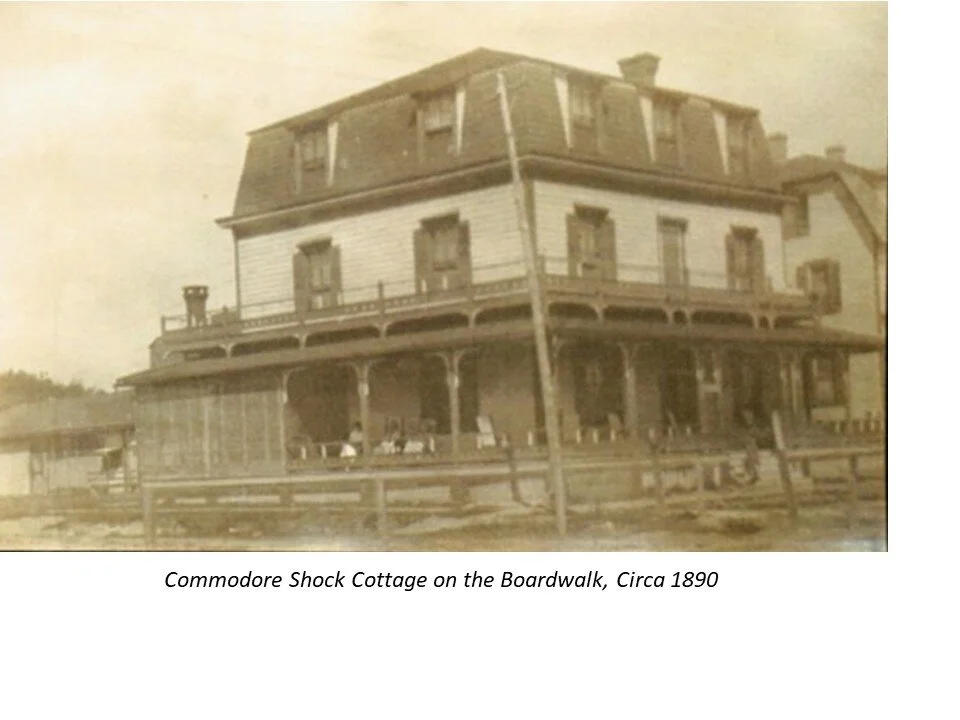

Deep among the archives held by the Rehoboth Beach Historical Society is a ~1905 sepia photograph of a stately residence on the Rehoboth boardwalk with the inscription, “Shock Cottage”. When I came across that photograph, the one available fact was that the person who owned this cottage was referred to as “Commodore”. The rank of Commodore is bestowed only to the highest ranking of naval officers.

One day last summer (2019), while sitting on the beach, I happened to comment to my son-in law that there was a picture at the Rehoboth Beach museum of a residence owned by a Commodore Shock who lived on the boardwalk. The subject came up naturally because Mike (my son-in-law) is a retired master chief in the navy. He took the opportunity, right there on the beach, to surf the internet for information. A few minutes later he showed me a picture of a person identified as “Commodore William H. Shock dressed in civilian clothes”. While he found nothing more about this fellow, I figured there must be more to learn. Little did I know that, had it been 100 years earlier, Mike and I could simply have turned around and looked up at the cottage of Commodore William H. Shock.

In subsequent weeks, my research would lead to significantly more information about the Commodore. What follows is that story.

Commodore Shock Invests in a “Cottage” at Rehoboth

At the end of his naval career, Commodore Shock’s permanent residence was in Washington DC. Given his naval career, it is not surprising that he felt the urge to summer in a “Cottage” at the beach, from which he could spend hour after hour gazing out to the sea that had been, for so long, the center of his life. From his front windows he could see both sailing ships and steam ships entering or departing the mouth of the Delaware River, servicing ports north including Smyrna, Wilmington, Philadelphia, and Trenton.

It is not known exactly when Commodore Shock purchased the lots on the boardwalk at the beach end of Olive Avenue. The location today (2020) is occupied by Obie’s by the Sea Restaurant. That property address, known at the time as lots #31 and# 32 Surf Avenue, was attributed to different owners in 1878. So it is guessed that the Commodore purchased the property with his wife in the early 1880s. Commodore Shock’s wife Sarah (Moody), with whom he had enjoyed a long and enduring marriage, died in 1883. Could she have been a part of his discovery of Rehoboth...possibly...but in any case, she sadly died before having much of an opportunity to enjoy the experience.

Commodore Shock In Service to His Country

By the time he reached Rehoboth, Commodore Shock had retired from a long and distinguished military career. He first entered the United States Navy in 1845 as a Third Assistant Engineer. Shock then served under the famed Admiral Matthew Perry during the Mexican-American War (1846 - 1848), including the decisive American victory at the Battle of Vera Cruz.

Positioned at West Point in the mid 1850s, Shock, as chief engineer, oversaw the construction of the famous steam powered naval ship, the Merrimack. The Battle of the Monitor and Merrimack, known as the “Battle of Ironclads” at Hampton Roads, was the most famous naval battle of the American Civil War.

Although essentially a stalemate, the battle is known as the turning point of naval history. It is described as the event that marked the transition by navies around the world from sailing ships to steamships. Shock was a prominent engineer at the center of that transition and at the peak of his naval engineering career.

Also during the Civil War, Shock served with distinction under Admiral David Farragut at the blockade of New Orleans. It was during that battle that Farragut uttered his famous phrase, “Damn the torpedoes; full speed ahead".

After the Civil War, Shock was active in the U.S. Foreign Service. He served in Europe, and he was one of the first Americans to land on Chinese soil. He also worked for a time on a coastal surveyor screw steamer, the Legaré, from which he may have gotten his first glimpse of the town of Rehoboth. In 1877 during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant, Shock was made the U.S. Navy Chief of Steam Engineering for the United States. He retired from the Navy in 1882. In that same year Shock published a book entitled, “Steam Boilers”. The book became the standard textbook on steam engineering for the United States Naval Academy.

Any one of the above related battles, admirals, locations, and ships on which Shock served, are significant enough to have been the subject of famous artwork. This writer leaves the reader to his own internet research to discover these interesting times.

At retirement, it is probably not incidental (given his career) that Commodore Shock would travel from his home in Washington, DC to Rehoboth by steam locomotive for the Washington to Annapolis leg; by steamship for the crossing of the Chesapeake Bay; then by steam locomotive again from Kent Island to Rehoboth. If any of those conveyances broke down he was in position to fix the steam engines so that the journey could continue.

But this story is not about Commodore Shock’s distinguished naval and engineering career. It is about his influence on the growth of a struggling new City, Rehoboth Beach, during its formative years at the end of the nineteenth century.

Commodore Shock as Commissioner Rehoboth Beach

What is perhaps surprising is that Commodore Shock, then 70 years old, was not ready to withdraw from public service. While his permanent and winter address was Washington, DC, the Commodore spent summers at his “cottage” on the Rehoboth boardwalk. His heart seems to have been in Rehoboth where he would serve for twelve years as a city commissioner. The death of his wife a few years prior would have left a void in his life, which is perhaps why the Commodore became so enmeshed in the governance of the town. Commodore Shock was intensely active during his tenure on the city board (1891 – 1903) and his participation was wide ranging.

Hand-written notes of city commissioner meetings, during that time, record where and when the meetings occurred, who attended, and what subjects were covered. There would be up to fifteen commissioner meetings per year, with multiple meetings during summer months. Out-of-season meetings would be held where commissioners lived in the winter months: Lewes, Wilmington, Dover, Baltimore, Washington...all of which were accessible by train. The meetings in Rehoboth were often called to order based on a commissioner’s “arrival on the noon train”; often adjourned with regard to the 3:00pm outgoing train. Many town commissioner meetings were held in Commodore Shock’s own cottage parlor.

Commodore Shock submitted letters of resignation from the Rehoboth Beach Board of Commissioners twice during his tenure. In December of 1893, he submitted a letter of resignation blaming his inability, for health reasons, to attend the winter meetings in other towns. But his letter was “laid on the table”. Commissioners concluded that his services were too valuable to the board and the taxpayers. Six years later, in September 1899 he again submitted a letter of resignation. It too was “laid on the table”. Shock would be re-elected to another three year term in the July 1901 election, two years after his second resignation letter.

It is separately noteworthy that at the start of the Spanish-American War in 1898 (famous for the cry “Remember the Maine”), Commodore Shock applied for re-commissioning in the navy. He was declined...perhaps because he was 77 years old.

Commodore Shock helped bring about the transition of Rehoboth from the Camp Meeting Association folks in May 1891 and was sworn in as one of the original commissioners of Cape Henlopen City that October. During his tenure, Shock attended well over a hundred Rehoboth Commissioner Meetings. He was on occasion compensated for expenses, typically $3 to $6, probably for train fare. Recounting Commodore Shock’s participation as a board member provides fascinating insight into life in Rehoboth during the last decade of the 1800s. The following paragraphs cover his activity by subject area.

Camp Meeting Association is Displaced

After what must have been several months, or years, establishing the justification for their action, in May 1891 Commodore Shock and fellow property owners in Rehoboth presented the Delaware legislature with a proposed “Articles of Incorporation of Cape Henlopen City”. Those Articles of Incorporation argued that “...the Rehoboth Beach Camp Meeting Association of the Methodist-Episcopal Church have partially abandoned control of said association...” It was further reported that “...the capital stock of said corporation {referring to the Camp Meeting Association} was by the provisions of said charter to be sold at the sum of fifty dollars per share; and, whereas, no consideration was ever, in fact, paid for said stock...thus violating said charter...” The legal wording continues to spew forth for several pages.

Those Articles of Incorporation were adopted by the legislature of State of Delaware and signed by then Secretary of State, on March 19, 1891. It was by that action that the “Camp Meeting Association”, which founded Rehoboth in 1873, was displaced.

The “Articles” specifically identified a group of seven men who were designated as commissioners of the new Cape Henlopen City...to be re-named Rehoboth City two years later. Most of them, if not all, were “freeholders” of property on Surf Avenue at the boardwalk. One of them was Commodore William H. Shock. He was sworn in as a commissioner on October 21, 1891. He was 70 years old.

Establishing Law and Order in an “Old West” Style Railroad Town

One of the Commodore’s highest priorities was restoring basic discipline in the town. Virtually every property owner had stables for horses and other livestock, chicken coops, and pig sties. Dogs were running free and a reported nuisance. On August 13, 1892 Shock made a motion that the storehouse be moved to Lot #49 Olive Avenue for the purpose of impounding livestock found roaming free on City property. The motion carried.

The Commodore personally oversaw the relocation of the storehouse and was compensated $3 for his expenses on the project. It is certain that the effort was helpful in improving City sanitation. But it was not entirely successful...as is evidenced by this picture of roaming livestock taken about fifteen years later!

Also in the context of “Law and Order’ Commodore Shock participated in other important resolutions:

· September 31, 1896: Property owners were instructed to remove all obstructions and fences, and to vacate City streets and avenues on which they had infringed, blocking the free flow of pedestrians, carriages, and delivery wagons.

· March 11, 1897: Shock makes motion to fill up and close any places that are held for illegal purposes, such as the “cave up in the woods”. Motion carried.

· July 12, 1899: Shock reported on vaudeville theaters, no permits had been issued and that such performances were objectionable.

One of the early actions by the first commissioners was to establish a police superintendent. On July 20, 1896 Shock moved that three badges be made up for use by special constables and dispensed as necessary by the superintendent. This was surely a reaction to the typically riotous behavior on the 4th of July. Firing of pistols needed to be controlled; fireworks west of the boardwalk had to be eliminated.

The commodore and Attorney Munn, also from Washington, DC were appointed to prepare a digest of by-laws and ensure their legality with the State Legislature. The digest was submitted in April 1897, approved by the Commissioners with 500 copies to be printed.

Building A Basic Infrastructure and Services for the New City

Commodore Shock worked on virtually every aspect of the new town’s infrastructure. He was a major participant in all of the following listed activities. Each of the subjects were important town issues between 1891 and 1903.

Boardwalk: The original boardwalk was built by the Camp Meeting Association in 1873. It was 1000 feet long, laid on the dunes, and eight feet wide.

By 1891 when the new government was formed it had fallen into disrepair. Shock repeatedly asserted that it needed to be repaired, upgraded, widened, and rebuilt. In 1892, Shock proposed that the State legislature be petitioned for authority to borrow on bonds to pay for its reconstruction. It took eleven more years for the boardwalk to be rebuilt.

Pilings: At least four different times during his tenure as commissioner Commodore Shock made motions to add a second row of pilings on the beach. His elegant wording (1892) was, “whereas the high seas have, in the past, cut away portions of the bluff, be it resolved that an outer row of pine pilings be cut from our woods and placed as a second row in a line with that already in place at the front of Mr. Water’s cottage”. It was perhaps Mr. Waters 1898 complaint that the commissioners had not taken sufficient care of the beachfront that made it happen. Waters owned the boardwalk cottage just at the north side of Rehoboth Avenue (where Dolles is today). This circa 1903 image shows how the boardwalk and pilings looked when the Commodore completed his tenure as commissioner. The picture is looking north from about where Mr. Waters cottage was positioned. The outline of the Commodore’s cottage roof is evident on the far horizon at the middle of the picture. Note that the boardwalk is built directly on the sand with no space between the beach and the walking surface.

Streetlamps: During the twelve years of the Commodore’s commissionership, oil streetlamps were individually lit by a lamplighter. Each lamp included a well for oil storage and a wicking system. As early as 1893, Shock had six lamps added to Surf Avenue. It was Commodore

Shock, of course, that later introduced the idea, in 1898, of contracting for an acetylene gas system that would distribute gas by pipeline throughout the city. The idea was tabled at the time, only to be installed just after his death in 1905.

Before Shock left office commissioners also entertained the idea of establishing an electric light grid. This earliest attempt to do so failed in favor of the acetylene system.

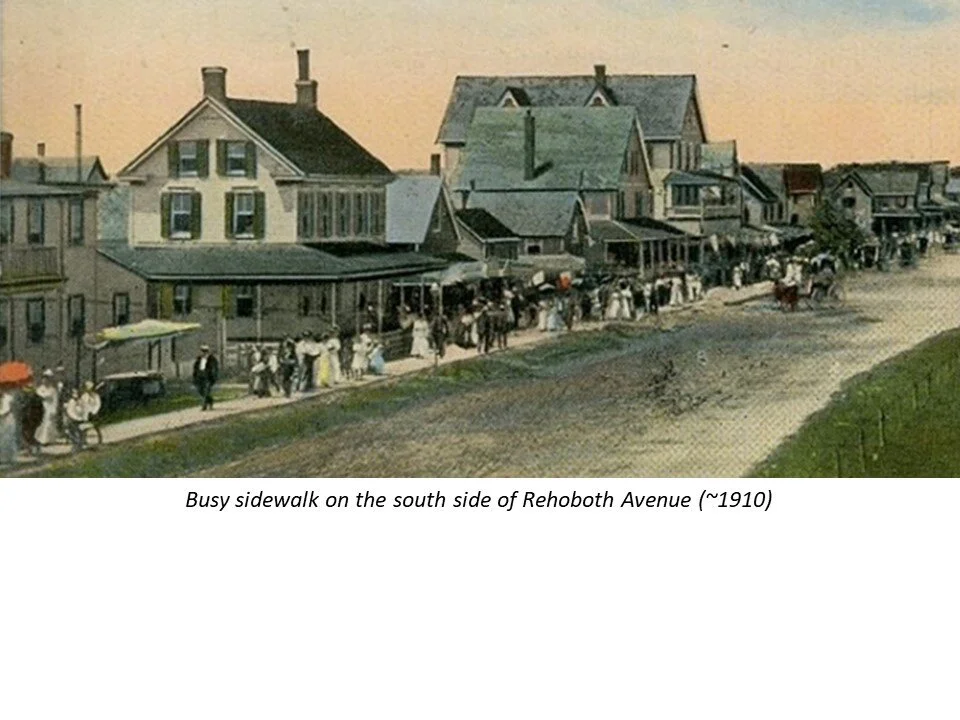

Sidewalks: The Commissioners, with Shock at the lead, made it a requirement of property owners of beach block lots between Lake Street and Laurel Street to install 4’ wide sidewalks of brick, lumber or other suitable material. The sidewalks were to be built at the property holders own expense. Some of those brick sidewalks exist today...look for them on Maryland Avenue.

Streets: All streets in Rehoboth in the last decade of the nineteenth century were dirt. Over his tenure, Shock made numerous motions relating to filling, cindering, leveling, or paving various streets in town. Dirt removed from the excavation of the canal was used to fill ruts in the streets. Cinders from the railroads’ steam engines were collected from the drop pit, located under the tracks at the water tower, for use on the streets. Those cinders were often still hot from the embers. In 1894, Shock moved that Henry Roach, the lamplighter and garbage collector, be also employed to remove brush and trees from 1st Street between Park and Columbia Avenues. Motion carried.

Sewage and Garbage: In 1894, Commodore Shock submitted a memorandum concerning levels of surface water on Lake Gerar, Gordon’s Pond, and Rehoboth Bay with a view towards establishing some system of sewage collection. Six years later in 1900 Commodore Shock was appointed to a committee to evaluate an engineering report on “Drainage of Rehoboth”. The report was subsequently approved, but there was no funding available at the time to create a sewage system. In lieu thereof, Shock provided instructions on how residents should dispose of various waste sources until bonding was approved. That took some time; it was not until the 1930s that a sewer system was finally installed throughout the City. Establishing a water distribution system was not even discussed during Shock’s tenure. Well water was stored in private water towers. In the late 1890s, a water distribution system might have been even more important than a sewer system because there was no effective means of fighting city fires. There was no fire department, nor any discussion of one. That is regrettable, given the number of devastating fires that took place during those times.

Mail and telephone: Commodore Shock was appointed in 1898 to call upon the postmaster in Washington, DC to request two mails a day in Rehoboth. He reported a successful outcome at a subsequent meeting. In 1899 Diamond State Telephone was authorized by the commissioners to erect poles and string wiring throughout the City. By 1910 twelve phones were in operation, mostly at the prominent businesses about town.

Establishing, Financing, and Staffing City Government

In 1891 Cape Henlopen City Corporation (two years later to be re-named Rehoboth Beach) was allowed to be formalized because the “Camp Meeting Association” no longer had financial control of the community. Commodore Shock was an important leader in re-establishing a viable government.

One of the first orders of business was to find the funds to accomplish necessary projects. In addition to re-establishing the ability to collect taxes, the commissioners knew that the properties owned by the governing entity itself, now Cape Henlopen City, had considerable value. The new commissioners had to wrestle away records, such as they were, from the previous association mangers. That would not be easily accomplished.

Once property records were recovered, however, the commissioners began to sell lots to generate funds. The Commodore was always involved in the process. The lots ranged in price by location, generating about $50 per lot in those early years. Sale of lots was not done indiscriminately. In 1896, a survey was ordered to clarify property corner locations. It was Commodore Shock, of course, that moved that the report be accepted. Quit claims were issued to those who could prove ownership interest in a particular lot. When lots were sold it was invariably done with a discount offered in exchange for assurance that the new owner would build on the lot...which was invariably agreed. Investing and holding for the purpose of taking advantage of increases in property values was discouraged. At one point an offer was made to the commissioners to purchase all city properties. The offer was declined. How different the city would have been from the Rehoboth we know today.

The Commodore was named to the committee that established assessed value of properties and was typically the person who made the annual motion that decided what rate of taxation on that assessment would be imposed for the upcoming year, typically 1.5% to 2%. Each year a meeting was held to allow property owners to appeal their assessments. Collecting the taxes was of course problematic and the elected tax collectors were compensated by percentage of funds accumulated. Accurate records were demanded by Commodore Shock, who at least once moved the Treasurer’s report be returned to be made more complete and to cover old taxes collected and due. Motion carried.

The sale of bonds was also used to generate funds. In 1895 Shock moved that the treasurer take up, at once, ten fifty-dollar bonds. In 1899 the Commodore submitted a circular to be sent to each taxpayer for vote; the purpose being to decide if the City should get bonding to do such things as introduce electric lighting, build a sewage system, and/or enlarge the boardwalk.

Commodore Shock was frequently the officer in charge of elections. Only freeholders were permitted to vote; no women of course. That amounted to about 13 voters in 1892, but as a result of the lot sales and growth of the city, the number increased to about 150 in 1903, the last year of the Commodore’s participation on the Board.

Recognizing that good management of the City required well placed staffing, Shock was the person who made the motions to add the following appointments to staff positions: James E. Marvel to be Superintendent (1893); Thomas Roach to be lamplighter (1894); Charles Richards of Georgetown to be town counsellor (1896); Charles Horn to be tax collector (1899); Attorney H. B. Munn to be President of the Board (1902)

On July 8, 1892, Shock was elected to be temporary secretary in the absence of Secretary Cannon. That lasted for several meetings. For this researcher that was fortuitous because the Commodore’s handwriting was immaculate, even artful, making his work easier than most to read. Note the careful structure of each letter and the manner with which he held the straight lines of text. His handwriting was surely honed by the preparation of the daily log books on the many sailing vessels on which he was the engineer. His hand seems to have become careless however at the signing of his own signature.

Special Projects Give Character to the City

The Rehoboth Beacon, the City’s own intermittently published newspaper, printed a brief synopsis of Commodore Shock’s career in its July 20, 1901 edition. His naval career is outlined. One sentence is devoted to his support of Epworth Church. A Single concluding line describes him as a summer resident “deeply interested in all that pertains to the well being of Rehoboth”. That is quite the understatement. In addition to the above mentioned leadership role he played in running the City, Commodore Shock was involved in a variety of highly visible projects that are notable among Rehoboth historians, some that are memorable and some that have been lost to memory.

Railroad Spur to Laurel Street: In 1891 William Bright led the new commissioners of Cape Henlopen City to carry a motion that allowed the railroad the right to condemn property for a spur of track from Rehoboth Avenue to Laurel Street. He would have needed Shock’s support to approve that action. Bright, along with Shock, was one of the original boardwalk property owners to transition the “Camp Meeting Association”. It is generally understood that the spur would serve a fish processing plant and block factory just south of the (then) southern end of the boardwalk. It also, rather conveniently, extended railroad service to within a half a block of Bright’s boardwalk hotel on Delaware Avenue (where Funland is today).

Another Cross Street parallel to the Ocean? In 1892, Commodore Shock proposed a new street be cut parallel to the ocean half way between Surf Avenue at the ocean front and 1st Street. He argued that then was the time since several of the affected properties remained “vacant of buildings”. The motion carried unanimously but the project never materialized as we can well attest today. Shock would raise the idea again in 1894 and in 1895. It is not certain why that would be so important to him.

Installing a Trolley Line on City Streets: In March 1903 the commissioners approved the proposal of William C. Lofland to install an electric railway on 1st Street. It would have extensions from 1st Street up Lake Avenue to the Henlopen Hotel, and from 1st Street up Brooklyn Avenue to the boardwalk. The use of steam locomotion on the line was specifically prohibited. Commodore Shock was in the last half year of his tenure as commissioner. In his one letter of communication with the commissioners after leaving office, Shock would ask about the status of the trolley contract (1904). Interestingly, subsequent boards of commissioners would attempt to contract with two other electric railway providers before 1910. These projects were never executed, of course, but it is fun to envision such a railway as a fixture in our town today.

Permitting of a Bath House on the Beach: In 1895, upon motion of Commodore Shock, the town commissioners leased space and permitted the erection of a bath house on the beach at the end of Baltimore Avenue. The franchise was requested by E. S. Hill, then the town policeman, to serve the needs of excursion parties. On weekends and holidays, the railroad would bring multiple car trains into the city, leaving day passengers off at the station on the center of Rehoboth Avenue. But they had no bathing clothes, so Hill’s Bath House was built to rent towels and the full body woolen suits that were the required beach wear. Shock also made the motion to extend the lease in 1903, with the provision that two salt water baths be added within two years. Though somewhat hard to pick out, Hill’s Bath House is shown at beach level in the center of this picture. Look carefully for the bathing suits hanging on the line to dry. The image also illustrates the rather well developed town along the boardwalk above the bathhouse.

Managing the Pavilion: Most folks with interest in Rehoboth’s history are well aware that Horn’s Pavilion commanded the space over the beach at the end of Rehoboth Avenue. Only a few of those historians will be aware that there existed a pavilion at that location long before Horn’s was given a lease to manage it. The original structure was in fact called the Pavilion and it was frequently the location for town elections and for commissioner meetings. It may have been first built by the Camp Meeting Association investors circa 1875 to 1880 as part of the original boardwalk. In 1897 Commodore Shock moved that, “...due to anxiety and needed repair without yielding revenue...”, the Pavilion should be moved to a more suitable permanent location. A year later however, it was resolved to receive proposals to lease the structure and the Commodore moved to have oak pilings added immediately to insure its structural integrity. Motion carried. It actually was completely remodeled.

Permitting Horn’s Fishing Pier: In 1901, Commodore Shock contributed his “Yea” vote to allow construction of a fishing pier off the back of what was then Horn’s Pavilion. Horn actually envisioned it for use as a steamboat pier as well, although it was never used for that purpose. The Horn pier was the first of two fishing piers constructed at the end of Rehoboth Avenue. Horn’s pier was destroyed in the 1914 storm, along with the Pavilion itself. The Pavilion was never rebuilt.

Religious Legacy

On approval of the Commissioners in July 1896, Commodore Shock purchased Lot #43 Rehoboth Avenue for $10 for use as a Sunday school. But that particular use was made unnecessary by the building of Epworth Church a year later. The location is now occupied by Browsebout Books.

In more than one way, Commodore Shock was a major contributor to the creation of the Epworth Church that survives and thrives today. The original church edifice was erected at 99 Rehoboth Avenue. At the time, the structure was carved out of farmland, quite apart from the hustle and bustle of the City. The church was dedicated on August 14, 1898. The picture shown here depicts its setting in ~1900. Today (Spring 2020) the Cultured Pearl Restaurant occupies that location, in what today may be described as quite the center of town.

Commodore Shock’s role included making the motion to the town commissioners, in August 1897, that “99 Rehoboth Avenue” be deeded for church purposes. He was also a large contributor of funding for the structure, along with his co-commissioner James Hooper. Commodore Shock is credited with having promoted Epworth to be the name for the church. Epworth was the English birthplace of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement. The church was dedicated on August 14, 1898.

Commodore Shock’s “Cottage” Ultimately Succumbs to the Sea, A Fitting End

From October 9 through 11, 1903, the same year that Commodore Shock finally left the Board of Commissioners; there was a storm that was described by then president of the board, Mayor Thompson, as the “most severe and damaging in the history of the beach”. A large portion of the newly installed boardwalk had fallen into the sea, as had a large portion of Surf Avenue. Commodore Shock’s cottage was noted as the point south of which there was total destruction of the boardwalk, with other sections destroyed north of his cottage.

It is interesting that the Commodore’s cottage itself survived that storm. And it is ironic that Commodore Shock had been, for twelve years, such an integral part of the construction of that new boardwalk, destroyed just three months after he left office.

As the postcard shown here confirms, Commodore Shock’s “Cottage” remains a centerpiece of the boardwalk scene two years after the 1903 storm. The picture was taken looking north from Horn’s fishing pier. The boardwalk was quickly rebuilt after the 1903 storm, fifteen feet closer to the ocean, but placed on pilings.

Yet another storm, on December 4, 1914, changed the scene forever. Pictures from both the north and the south, taken from what would have been Surf Avenue locations prior to the storm, assure that Commodore Shock’s cottage also survived the 1914 storm. The outline of his cottage roof is evident in both images below. Commodore Shock had passed nine years prior to the date of these images.

On November 6, 1909 the Board of Commissioners issued quit claims on the lots where Commodore Shock’s Cottage stood... 32 Surf Avenue, and 1 and 3 Olive Avenue. The quit claims were issued to A. B. Mayer and William D. Denny, clarifying the title of the properties they had purchased from the estate of “the late Commodore Shock”. Shock’s long time attorney friend from Washington DC, Commissioner Munn was present at that meeting.

After much discussion and controversy, Surf Avenue was abandoned after the 1914 storm. Horn’s Pavilion and the fishing pier were irreparably damaged by the storm and eventually razed. Hill’s Bath House must have been totally destroyed. As the image portrays, at least some of the boardwalk itself survived, in testament to the decision made after the 1903 storm to move the boardwalk 15 feet closer to the ocean but to elevate it on pilings. Shortly after the storm City Commissioners passed an ordinance that no structures be permitted for locations east of the boardwalk.

In 1920 another major storm hit Rehoboth.The entire boardwalk, at least that north of the Belhaven Hotel at Rehoboth Avenue, was swept out to sea.

Shock’s wooden structure cottage would have been thirty-five years old and subject to relentless and fierce coastal forces the entire time…but it survived. An advertisement several years later confirms that the “Shock Cottage” was used as a guest house after he passed. A 1930 picture of the boardwalk would confirm, at a minimum, the Cottage had by then disappeared.

Commodore Shock’s Final Years

Commodore Shock’s extended term as a commissioner of Rehoboth ended in July of 1903. His final meeting, fittingly, would be held in his own boardwalk cottage parlor on July 10, 1903. His last official motion was to tender a vote of thanks to President H. B. Munn for impartial leadership and deep interest in the well-being of Rehoboth. The motion was unanimously carried. The Commodore had made several similar “votes of thanks” during his twelve year tenure as commissioner. But he himself was never to be made the subject of such a commendation for his service as a Commissioner. It can only be hoped that was done in a private setting.

In 1897 the Commodore sold a lot at 25 Columbia Avenue, which he had owned separate from his boardwalk cottage, to his son Wilton for the going price, $50. Wilton died two years later in 1899. That was five years before the Commodore’s death. Surely this added to the Commodore’s disheartenment at the end of his life. There would be no heirs to his property in Rehoboth.

Commodore Shock died in Washington, DC on December 18, 1905, two years after his last meeting as commissioner. He was buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, his birth city, beside his wife Sarah. In the four-page single spaced obituary by Rear Admiral Baird, Commodore Shock’s naval career accomplishments were heralded. Neither his time and service, nor even his existence, in Rehoboth, was mentioned.

Epitaph: No question Commodore Shock had an extraordinary naval career, but it is unfortunate that it overshadowed his time in Rehoboth. He might rightly be remembered as a (maybe “the”) Founding Father of Rehoboth Beach. He brought to Rehoboth the discipline to which he was required to adhere as an officer in the navy... establishing law and order, fiscal responsibility, and governmental oversight...in what must otherwise have been a riotous “old west” style railroad city. He recognized the vital importance of the boardwalk as the life blood of the resort community. The Commodore’s work established the foundation upon which our thriving City is built today.

Reference Sources

Commissioner Meeting Minutes, Book 1891-1904, City of Rehoboth

Methodism in Rehoboth Beach, Pamphlet by John Gauger, Epworth Church Historian, Published 2018.

Obituary, National Engineers Journal, pg 351.

Rehoboth Beach Tittle Tattle, Vol 1 (#1), June 1, 1912, published in Rehoboth.

Ancestry.com research (2019) by Donna Vassalotti, Rehoboth Beach Historian

Except as noted hereafter, all images used in this article are owned by and attributed to the Rehoboth Beach Historical Society, Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. In order of appearance, the other images are attributed as follows:

Sketch of Commodore Shock, Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1600-1889

1862 Battle of Hampton Roads, American Civil War: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hampton_Roads

1890s Boardwalk, Purnell Coll. DE Archives (2), Dover, DE.

1914 Storm Damage: From an album of pictures collected by Peck Pleasanton, who was the owner of Pleasant Inn at the corner of Olive and 1st Street, Rehoboth. The album is now in the possession of Keith Fitzgerald of Rehoboth and owner of Back Porch Restaurant.

1920 Storm Damage (pic taken from Olive south), My But the Wind Did Blow (Pg 22) by Jim Meehan (2003), Harold Dukes, Publisher.